By Laura Kim and Angela M. Antonelli

Planning for retirement is not a one-size-fits-all model. While savings, health, cost of living, and lifestyle expectations are major factors, research shows that gender can play a large role in retirement planning and that women may have additional challenges that should be considered. On average, women will live longer than men, spend more years in retirement as single, spend more money on healthcare, have lower earnings and savings, play a larger caregiving role that may lead to more part-time work, have more work gaps in their careers, and have a greater reliance on Social Security upon retirement.

These factors exacerbate the current challenges of living a longer life with inadequate savings and can create a greater sense of retirement insecurity for women. Policymakers and individuals have to consider these factors as they develop new approaches to encourage and enable more individuals to plan properly for retirement.

Most women will outlive their spouses and face higher costs in retirement

Women have a longer life expectancy than men: On average, 65-year-old females are expected to live to 86.7 years, which is more than two years longer than men. For a couple reaching age 65, the woman will outlive her husband by 11.5 years on average, due to age gaps between married men and women. Oftentimes, this leaves the woman to bear the costs of many household expenses that may have been based on an income previously shared with a significant other.

Another cost driver for women, especially those who are elderly, is healthcare. According to HealthView Services, a 63-year-old woman is likely to spend roughly 30 percent more in total lifetime retirement healthcare expenses than her husband. This is not only because women live longer, but because they are more likely to suffer a chronic illness and less likely to benefit from the unpaid services of a spouse-caretaker. These figures are especially troubling given the forecast that healthcare expenses will rise 5.47 percent per year over the next decade.

Women face an earnings gap and challenges to building wealth

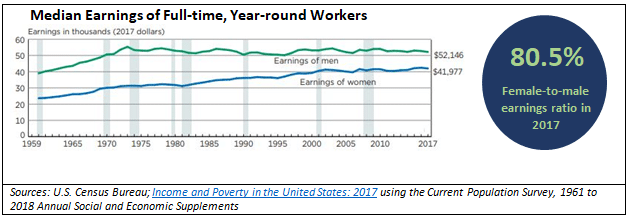

On average, women earn less than men. This earnings gap has a compounding effect on women’s ability to save and build wealth over a lifetime. In 2017, the median earnings of women working full-time and year-round in the U.S. was 80.5 percent of men’s median earnings. While this is a significant improvement since 1981, when the gender wage gap was 59.2 percent, progress in closing this gap has slowed in recent years.

The effect of the earnings gap is especially significant for households where mothers are the sole breadwinners. In 2014, 40 percent of families with children under 18 relied primarily or only on the mother’s income. At the lowest quintile of households, with annual earnings of less than $21,600, women’s income comprises 89 percent of their families’ total earnings. Single-mother families are the most likely to be in poverty (28.4 percent), more than five times higher than for married-couple families (5.2 percent).

In 2014, 40 percent of families with children under 18 relied primarily or only on the mother’s income.

The earnings gap may seem surprising, given that women have earned more bachelor’s degrees than men since 1981. But the reality is, even after accounting for factors including education, occupation, and experience, women still earn less than men in comparable positions. This dynamic leads to average lower earnings for women and has a negative impact on their ability to save for retirement.

Women are more likely to face additional career disruptions

Life events such as marriage and children have drastically different consequences for women and men. Married women are less likely to be in the workforce than women who have never married, are divorced, or are separated. Married men, on the other hand, are more likely to be in the workforce. Similarly, the presence of younger children corresponds to less employment for women and more employment for men. The younger the child, the greater the likelihood the mother is not in the workforce, while men’s workforce participation rates are not associated with the ages of their children.

Elderly caregiving also falls disproportionately on women, and many disruptions from caregiving responsibilities negatively affect female labor participation and wages. The typical caregiver is a prime–working-age woman providing 20 hours of care per week to one or both of her parents. According to a 2013 Pew Research Center survey, many more women than men reduced work hours to care for a child or family member, took time off, quit their jobs, or turned down a promotion. As a result, women were twice as likely as men to say that taking time off hurt their overall careers.

Career disruptions in midlife have substantial consequences in retirement because people not only forego income, but also lose out on work-provided benefits such as health insurance and employer-sponsored retirement plans. Women who leave the workforce at age 50 or older to care for a parent are estimated to lose an average of $300,000 in lost wages and benefits over their lifetime.

Other factors reduce saving and earning opportunities for women

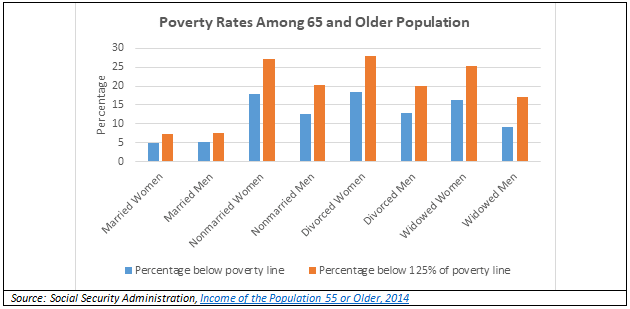

Women save lower amounts because, on average, they have less ability and opportunity to save, not only due to the factors associated with long-term workforce participation, but also due to more unstable work, greater debt burdens, and increased vulnerability to life events compared to their male counterparts. For many elderly women, the compounding disadvantages include less individual savings, lower Social Security income, and fewer benefits from employer-sponsored retirement savings plans. These factors contribute to creating a higher risk of living in poverty for elderly women than for elderly men.

While women account for 47 percent of the workforce, they make up nearly two-thirds of part-time workers. Part-time work does offer a more-flexible work schedule compared to traditional work arrangements, but part-time workers are less likely to have access to benefits, such as paid time off, health insurance, and employer-sponsored retirement savings plans. These workers are also more likely to experience unstable and irregular work schedules. In fact, an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau data by the National Institute on Retirement Security shows that working women are more likely than men to be working for an employer that offers retirement plans, but this is overshadowed by the fact that women are less likely to be eligible for those plans than men.

Debt is another factor disproportionately preventing women from building wealth. As more women pursue higher education, student loan debt among women has skyrocketed. Of $1.3 trillion in total U.S. student loan debt, women hold two-thirds of this debt. Not only has the cost of higher education continually increased by more than inflation rates, but women are on average more likely to take on larger student loans than men. This, coupled with women’s lower average earnings, means it takes women longer to pay back such debt, which in turn increases the size of the debt. It also increases the risk that saving for retirement will become a lower financial priority for women.

Divorce is a life event that disproportionately affects women’s retirement security. Because men have higher earnings on average and more savings through workplace retirement plans, divorce is harder financially on women. After a divorce or separation, household income decreased by 41 percent for women in or near retirement, compared to a 23 percent drop for men. Widowhood had a similarly negative impact on women’s household income.

Overall, women 65 and over are more likely to live in poverty at significantly higher rates than their male counterparts. Almost one-half of elderly unmarried women receiving Social Security relied on their benefits for 90 percent or more of their income, compared to 22 percent of all seniors, in 2014. In addition, women generally receive lower Social Security benefits than men because they work for fewer years and receive lower pay. In 2015, the average yearly Social Security benefit was $14,184 for women, compared to $18,000 for men.

Conclusion

A key element to improving retirement security for all requires understanding the need to tailor opportunities to meet the unique challenges faced by workers. One size does not fit all. As policymakers and employers come to understand how women’s experiences differ from those of men, there are steps they can take to begin help women prepare better for retirement.

Financial education and services that help women understand how career-disrupting life events (such as family caregiving) can negatively affect their retirement savings trajectory may help improve short- and long-term financial planning decisions. Policymakers also should consider how to help preserve and expand access to retirement savings options. For example, several states are now offering simple, low-cost retirement savings options for workers who currently lack access to an employer-sponsored plan. In addition, policymakers should examine how existing policies and resources can be better utilized (e.g., spousal IRAs) to maximize savings and better help those workers who may need to move in and out of the workforce to address other needs.

If the goal is to help all workers attain financial security in retirement, policymakers, plan sponsors, and providers can do a better job of offering more-flexible options that allow more women to consistently maintain access to a way to save for retirement.

Laura Kim is a Research Assistant with the CRI and received her Master’s degree from the McCourt School of Public Policy in 2016. Angela Antonelli is the Executive Director of the CRI. The authors would like to thank Sarah Belford, former research assistant, for her research assistance.

September 2018, 18-05

Additional Resources

National Institute on Retirement Security, “Shortchanged in Retirement: Continuing Challenges to Women’s Financial Future,” March 2016.

The Society of Actuaries and WISER, “The Impact of Retirement Risk on Women,” 2014.

TIAA, “Income Insights: Gender Retirement Gap,” October 2016.

U.S. Department of Labor, Women’s Bureau, “Issue Brief: Women’s Earnings and the Wage Gap,” 2017.

U.S. Government Accountability Office, “Retirement Security: Women Still Face Challenges,” July 2012.